The Architecture of Santa's Workshop

How do we know what Santa's Workshop looks like if none of us have ever seen it? Children who imagine what Santa's house looks like grow up to become the artists and writers of the next generation who create the next images and stories of this magical place. The architecture of Santa's Workshop has changed over time.

The earliest image of Santa's Workshop at the North Pole appears in a two-page cartoon by Thomas Nast. In the drawing "Santa and His Works," printed in the Christmas 1866 issue of Harpers Weekly, the artist envisions many never-before described activities of Santa's daily life: crafting toys, spying on naughty children with a telescope, recording their merits in a ledger book, and other details of the job. A small panel above Santa contains a drawing of a quaint little village labelled as "Santa-Claussville, N[orth] P[ole].

In Nast's imagination Santa lives in a European-style village with a church and apartment buildings. The buildings are surrounded by stubby pine trees, stiff farm animals and milkmaids. The drawing more like a toy village made of blocks than a realistic place. Perhaps the artist was directly inspired by his own childrens' toys. Like so many other details of the legend of Santa Claus, the idea that Santa lived at the exotic and far away North Pole is a simple but influential fancy of Nast's imagination that went on to become widely-accepted idea about the jolly old elf.

In 1902, L. Frank Baum penned The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus as a follow-up on his successful fantasy The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. The book describes Santa's journey from foundling to fame and immortality. Claus discovers his calling by accident, after making a toy to comfort a lonely child, but goes on to win the admiration of all the children of the world.

The book places Santa's Workshop in faraway Laughing Valley, but provides no description of its appearance, other than a few drawings of the interior by illustrator Mary Cowles Clark such as the one shown above.

Department store window displays have been a long-standing holiday tradition since Macy's in New York first set up a temporary holiday display in 1862. By the 1890s the holiday window had become a popular nationwide phenomenon. The earliest windows simply featured store products in an attractive decorated setup, but over the years the displays have become increasingly elaborate and focused on theatrical scenes rather than the actual items for sale in the store.

Santa's Workshop is a common window theme, featuring moving puppets building miniature toys, such as in this 2010 window at the Hudson's Bay store in Toronto. Through the glass, the viewer peeks into another world where scale and time seem to operate differently. As this little world only exists within the confines of the window box, Santa's Workshop has no external architecture, only a magical interior space which is opened up to our view by the replacement of the "fourth wall" of the space by oversized plate glass windows.

Across the Atlantic, Lewis's Bon Marche department store in Liverpool in 1879 created a full-size holiday display which visitors could enter. Owner David Lewis imagined the "Christmas Fairyland" as a thank-you for loyal customers and a chance for children to visit with a real-live costumed Father Christmas and actors dressed as elves. As the name suggests, the appeal was likely not just the visit with the jolly elf himself but the enchanting space around him. The temporary attraction was such a hit that it continued at the Bon Marche for over 125 years, until the store closed in 2007. The Liverpudlian Father Christmas had been greeting children for over fifty years when this photo was taken in 1930:

In the Bon Marche display and others that copied the concept in the UK and Australia, Father Christmas is imagined to live in a cavern or grotto under the ice at the North Pole. There is no exterior architecture of the Christmas Grotto, only a magical interior space which can fit any fantasy of the set designer. At the department store, temporary walls are set up in a large banquet hall or open room to create a narrow maze-like meandering path leading toward Father Christmas. In darker lighting the basic architecture might be used as a haunted house display, but the decoration of the Grotto emphasizes charm, surprise and exotic fantasy. Displays often feature animatronic moving figures, miniatures and toys lit by twinkling lights. In the U.S., some department stores featured indoor fantasy displays with a theme or story to create a similar attraction, but other displays are simply a disconnected series of diversions to entertain visitors waiting in a long line to see Father Christmas at the end. Because the exterior architecture of the Christmas Grotto is unseen and amorphous, the temporary walls can be installed in any large space such as a warehouse or shopping mall, which sometimes intrudes on the intended charm of the interior displays.

Disney's "Silly Symphony" short film Santa's Workshop from 1932 finally provides a clearer exterior view of Santa's Workshop. This picturesque snowbound castle is part castle and part industrial factory, a confection of spires and factory chimneys basking in the glow of the aurora borealis. In the foreground, snowshoed postal elves arrive one by one, bearing childrens' orders for making more toys. It is a happy scene of Depression-era productivity and full elf employment.

Inside the workshop, the elves are building the toys by hand as they've always done, but a few new assembly-line workstations create repetitive movements suited for the looping style of early Disney animation. The lugubrious movements of the laborers, as well as Santa's infectious laugh, create a joyful and fun mood at this modern mass-production factory. The film is marred by some outdated 1930s racially stereotyped characters, but is otherwise a playful vision of Santa's Workshop. In Scandinavia the yearly TV broadcasts of this film have been an anticipated family event for decades.

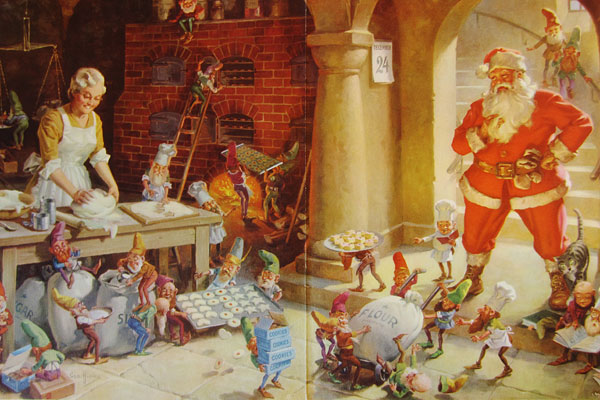

The Milwaukee-based illustrator George Hinke produced a wide variety of oil-painted illustrations for Ideals magazine from 1944 to 1953. His paintings of Santa's Workshop for the annual Christmas Ideals issue are the best known nowadays. Like artist Thomas Nast, Hinke drew on his childhood memories from Germany to add believable details to these busy scenes of life at the North Pole. Hinke imagines that Santa's workshop is a towered castle reminiscent of romantic Neuschwannstein, made of solid stone but perhaps floating on a cloud of fantasy. The interior scenes of the workshop are best known, as these images are a delight of warm details and humor.

In 1958 Ideals collected Hinke's Christmas paintings in the book Jolly Old Santa Claus which was a great seller and is still in print today. The illustrations have been reproduced on jigsaw puzzles, calendars and other memorabilia, and are familiar to many generations of children. Similar to popular German Wimmelbucher, there is much to discover by wandering your eyes about the paintings. Certain characters such as little Jingles and Whiskers the cat can be spotted in each scene. The brownies are all busy with their work or mischief, in a mixture of serious and slapstick activity. Although a large percentage of the workforce seems incompetent and accident-prone, Santa's cheeks are always rosy and the toys are always ready to deliver by Christmas Eve.

In early 1930s, entrepreneur Milton Harris began building a year-round Christmas attaction in the small town of Santa Claus, Indiana. Envisioned as a sort of World's Fair for children, with exhibition buildings promoting toy and candy companies, Santa Claus Town opened to the public in 1935 with Santa's Candy Castle as the first building, sponsored by the Curtiss Candy Company.

This Santa's castle is a squat brick structure of round turrets, with details similar to middle-class storybook Tudor houses built in many midwestern cities and suburbs in the 1920s. Several additional toyshop buildings and a Santa's Workshop were added in the following years. The commercial emphasis of the park spurred businessman Carl Barrett to build a rival Santa Claus Park nearby with his own vision of what children wanted. These competing attractions squabbled over the True Meaning of Christmas in endless lawsuits, to the detriment of both. A third Christmas attraction opened nearby in 1946, out-doing its predecessors. Santa Claus Land amusement park, later renamed more broadly as Holiday World, is still open today and is arguably the world's oldest theme park.

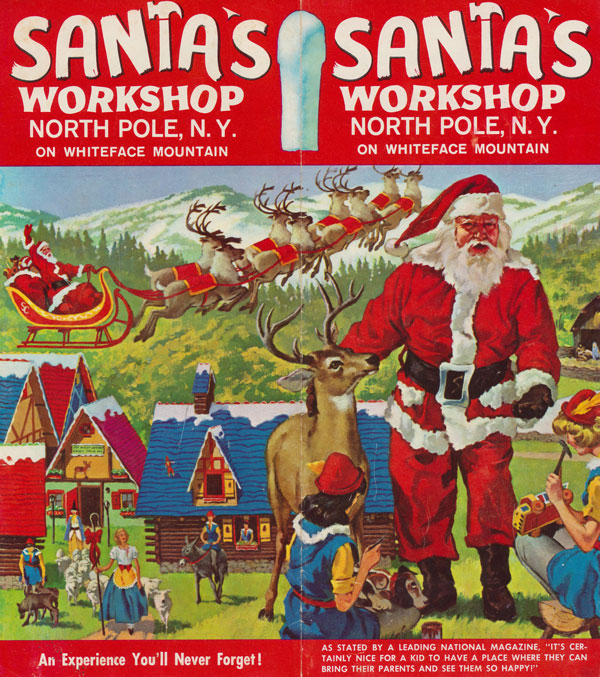

The success of these year-round Christmas attractions inspired many other Santa's Villages around the country in the 1940s and 50s. In the Adirnondack mountains, businessman Julian Reiss opened Santa's Workshop in 1949, a collection of steep-roofed log chalets populated by costumed elves, Santa, and storybook characters.

The attraction landed its own post office for sending letters to Santa and the town of North Pole, New York was created. In the center of the village is a stout outdoor refrigerated post covered by thick ice which is the literal north pole of North Pole, NY. In the early days of the park, animals such as sheep, goats and reindeer roamed the village freely among the tourists, creating the first petting zoo.

Most of these Santa's Village attractions were small family-run operations. Eventually the upkeep of the ersatz workshop buildings, costumes and activities proved unafforable to many operators after their heyday in the 1950s. How quickly the colorful charm of the Christmas Village turns to creepy decay! Only a handful of these early theme parks survive today.

The Santa's Workshop in the 1964 B-movie classic Santa Claus Conquers the Martians looks lifted from one of these home-made Christmas Village theme parks.

A newscaster reports from the scene outside the workshop, just a few feet away from the polar geographic marker. The workshop, seen in the background on the right, is a boxy shed with Tudor windows and polka dots, seemingly built from plywood.

Inside Santa's Workshop, three lone elves toil away building toys by hand amidst a clutter of toy parts and wood shavings. Clean up your work space, elves! Good housekeeping promotes workplace safety! Shortly after this scene, chaos ensues when the Martians invade to kidnap Santa Claus. Despite the film's low budget and hokey acting, John Call plays an admirably jolly Santa Claus.

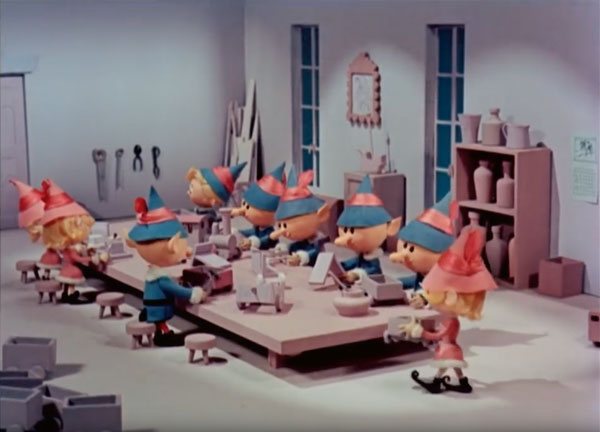

Also in 1964, Rankin-Bass released the animated TV special Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. In this Santa's Workshop, there is little decor on the pastel walls to distract the viewer from the characters in their gender-specific uniforms. With its low elf-sized tables and plain walls the workshop appears a rather drab work environment. It's no wonder that young Hermey is unhappy making toys here.

There are only brief glimpses of the exterior of Santa's Workshop in the Rudoph special, but in other Rankin-Bass animated TV specials such as Santa Claus Is Comin' to Town (1970), viewers get a better view of a 3-dimensional castle workshop and toy factory set up by Kris Kringle at the north pole.

Each subsequent sequel features slightly different sets with added outbuildings and and more-elaborate castles. When these animated specials were created, they were only screened once a year, and viewers had only a few brief glimpses of Santa's Workshop to fuel their imagination of its appearance until the next year.

Nowadays, with more media channels and more mediums for watching programs, the Christmas film genre has expanded with options to meet the demand for entertainment reminding viewers yet again to treasure precious holiday moments. Many new films looking for new storylines about Santa Claus have also explored the world of Santa's Workshop in far more depth than previous stories. In 1994's The Santa Clause, Tim Allen gets a first look over this vast world of wonder hidden beneath the ice at the North Pole.

The large set of Santa's Workshop in the film must have been expensive to create. At workbenches stocked with every manner of plaything, child elves tap their tiny mallets to assemble the toys and try to look busy. Up above on the far balcony, elves are baking cookies, while down in the pit below, others are experimenting with chemistry sets for no apparent reason. The North Pole Railway provides public transit for the workers to commute to their stations. Through the candy-cane doorway we can see the gift-wrap department. This workshop looks like a fun place for kids to play and goof around, like an oversized FAO Schwartz toystore with all the fanciest novelties that only rich kids can afford.

In the barely-watchable sequel in the trilogy, The Santa Clause 2 (2002), the filmmakers had a larger budget to build a bigger Santa's Workshop and hire many more child extras. Here the workshop is a stylish Art Nouveau pavilion on a snowy plaza in the middle of a quaint village of fin de siècle candy buildings. The workshop is exuberant and organic inside and out, and must have been fun for the set designers to create. The reindeer stable below the workshop in particular is a surprise homage to Gaudí, with stone columns inspired by the lower level of the Park Guell in Barcelona. The fanciful design of this Santa's Village deserves far better than being trapped in this grim clunker of a movie.

The 2004 film The Polar Express, based on the picture book by Chris van Allsberg, howcased a new computer-generated image of what Santa's Workshop might look like. In the image above, thousands of cloned elves gather on the main plaza at the north pole to await the arrival of Santa's sack of toys. The clock tower on the left is patterned after the Administration Building of the old Pullman rail car factory in Chicago, with other buildings inspired by the brick houses and arcades of the surrounding Pullman company town designed by architect Solon Beman in the 1880s.

The nerve center of Santa's operation takes place in an enormous Beaux Arts hall reminiscent of New York's lost Penn Station. No longer does Santa use a telescope to monitor the naughty or nice children, now he employs a vast array of closed-circuit televisions to monitor them and record their deeds on banks of teletype machines.

The motion-capture animation technique of the human and elf characters in The Polar Express may look a bit stiff or primitive to our eyes just few years later, due to the limitations of computer graphics at the time, but the style fits with the chilly and distant atmosphere of the slightly haunted architecture of the film. The children are simply brief trespassers at this remote citadel, not participating in or understanding how it all works as they hurry through the adult relics of grandiose but deserted streets and factories. This Santa's Workshop is a pre-digital world of dusty and antique machinery, frozen in time at moment before midnight Christmas Eve. Modern post-industrial reality is chugging ever away from that grand old era of industrial railroad America, just as the memories of dreams fade in the morning and children distance themselves from Santa and Christmas innocence when they grow older.

The film Fred Claus (2007) provides a less melancholy view of Santa's Workshop just a few years later. This North Pole is a sprawling computer-generated medieval village centered on the church-like dome of Santa's Workshop. By this time, CGI technology was advanced enough to create realistic images of just about any architecture imagined by film art directors.

Like The Polar Express, this Workshop design takes inspiration from Victorian architecture and antique industrial technology. In the vast post office at the North Pole, armies of elves receive letters to Santa through brass vacuum tubes. The characters are played by live actors, but their heads are often enlarged by special effects to make them appear "elf-like", which adds to a sort of goofy not-too-serious vibe to the film.

Unlike real-life Victorian factories, there are no clouds of soot and coal smoke in the air. The shop floors are bathed in clean and clear arctic light from high arched factory windows (despite the 24-hour darkness at the North Pole in winter time). The elves appear cheerful and bouyant in their work, not dulled by 12-hour shifts and six-day work weeks. The workers even have time and energy to have an impromptu dance party on the factory floor with Fred.

The real sets of the film may lack the detail and strong design of the computer-generated versions seen in long shots, but the colorful industrial cathedral style of the workshop evokes a feeling of cheerful busyness without drudgery. Indeed, the conflict of the film is provided by a business consultant who is overly concerned about numbers and the serious questions of whether Santa's operation is working efficiently. Viewers likewise are advised not to get hung up on the inefficiencies in the film's dialogue or characters, but to just let go of old grudges against sentiment and Santa Claus's complicated family.

Though computer-generated imagery can allow filmmakers to dream up wildly-extravagant workshops for Santa, some holiday movies set at the North Pole have chosen a more low-tech vision. The 2010 direct-to-video talking-dog-themed film The Search for Santa Paws takes us to a workshop where smiling elves in cozy felt tunics look busy while Santa himself finishes a song and dance for his birthday.

This workshop doesn't reveal the secrets of how the toys are made. They appear fully assembled from openings above and slide down chutes to be packaged by the elves below. It looks a bit like a cluttered toy store gift shop, similar to the set of the first Santa Clause movie except with flatter colors and fewer details to intrigue the viewer. I'm sure this set was expensive to create, but the overall look of the place is more ordinary than magical or fantastic.

The film Elf (2003) imagines a minimalist but cozy Santa's Workshop. This workshop appears to be a real-world set created without elaborate special effects. In many scenes, Buddy (Will Ferrell) appears larger than the other elves simply because he is placed closer to the camera, not through computer-generated editing. Rather than filling the room with hundreds of extras to tackle the overwhelming demands of every child on earth, the film focusses on the friendly family of elves who are able to magically turn out enough toys to meet world-wide demand.

The log walls of the work area are reminiscent of the monochromatic set of the 1964 Rankin-Bass Rudolph special, but with warm touches of craftsmanship in the scalloped roof beams and the ornamental Scandinavian tile stove in the corner. The toys here are all hand-crafted as well, with the joke being that each seemingly mass-produced plastic Etch-a-Sketch is carefully filled with sand by a diligent elf. Buddy feels guilty that he is not able to keep up with the astounding production rate of his fellow elves, but he is gently reassigned to a different work area rather than fired from the job.

A few years after the film was released, photographer Michael Wolf's series "The Real Toy Story" showed the real-world workshops where many of the toys we assume are machine made are indeed put together by hand. Legions of uniformed workers sitting at long tables not unlike the ones pictured in Elf paint the small parts one by one and assemble the plastic pieces of all kinds of toys. Wolf's exhibition of the photos included thousands of toys which were assembled at factories in China, providing a concrete connection to the workshops where mass-produced toys are created and the workers who assemble them.

More recently, numerous exposés of iPhone factories in China have revealed the harsh working conditions where these electronics are created. The little Etch-a-Sketch-like devices which seem so sleek and pure in design are also assembled by hand in sprawling factory cities employing as many as 350,000 workers. Many workers come from impoverished rural areas to work in the factories, so that the jobs are in demand even if the pay is low and housing and working conditions are not ideal. Unlike Buddy the Elf, anyone who falls behind is let go, and the boss's sympathies are with the buyers above him who demand productivity above all else.

![]()

Perhaps the idea of Santa's Workshop has become so familiar to modern children that it is tempting for writers and artists to re-invent it. Some recent holiday films have re-imagined a workshop radically different from the way Thomas Nast sketched it over 150 years ago.

The British animated film Arthur Christmas (2011) reimagines Santa as captain of a high-tech space ship instead of a sleigh. Like other British Christmas grottos, this workshop is built into a cave under the ice, so it has no visible exterior architecture. The mission control room seen below tracks the movements of Santa's space sleigh and monitors which children are naughty or nice. The central ziggurat made of ice has room for thousands of elves sitting at computer desks and is topped by a monumental ice carving of Father Christmas.

Another wildly untraditional take on Santa's workshop can be seen in the 2012 movie Rise of the Guardians. In the film, Santa Claus, a.k.a. Nicholas St. North, lives in a formidable multi-story palace encased in ice hanging off a mountainside in the far north. Santa has just launched his sleigh from a roller coaster-like chute emerging from the mountain below the workshop.

In this version of Santa's Workshop, the toys are not made by elves, but by clever yetis. And Santa Claus is not the jolly elf of Thomas Nast's time, but a tough tattooed strongman, brandishing sabers and driving his sleigh with gusto. The movie delights in overturning our assumptions about folkloric characters, although the end result is that all of them become super heroes in an action movie, more than the mysterious figures of legend who might live on in the imaginations of generations of children.

Santa's Workshop can be visited in the imagination of children and adults, but that imagination changes over time. The vivid imagery of its architecture is created for the most part by adults, and no doubt strongly influenced by ideas created in childhood. What will today's children imagine Santa's Workshop to look like when they are older? What do you think Santa's Workshop looks like?

Order the Santa's Workshop model book

Order the Santa's Workshop model book

Dover Publications, 2017: ISBN 978-0-486-81902-0. Paper model ©Matt Bergstrom, Wurlington Press